With the threat of global warming more prevalent than ever before, Medina spoke to Peter Jackson and Anne Coles about the timeliness of the new edition of Windtower.

Windtower offers a unique insight into a past way of life, exploring Dubai’s rich and storied past and heritage. This new and extended edition celebrates the 50th anniversary of the formation of the United Arab Emirates, diving deeper into the merchant community’s central role in Dubai’s pre-oil economy and social life. The new edition also considers the lessons to be learned from Dubai’s traditional windtowers at a time of global warming and climate crisis, and how this knowledge might benefit contemporary urban design.

What is different about this new edition?

While it is essentially the same book that we wrote fifteen years ago, Windtower has been very much brought up to date as well as being extended with a new and important chapter. The windtower district has actually been renamed Al Fahidi, after the nearby fort. We overcame this by accurately referring to Al Bastakiya quarter within Al Fahidi district.

The new second chapter focuses on the contribution made by Bastaki merchant families to the early growth and economic success of the town as a trading port in the Lower Gulf. This enabled us to broaden our research by including additional stories of some of the significant and wealthy merchant families, providing a more rounded and richer picture of the life and role of the Bastaki community in Dubai.

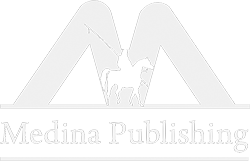

We have reviewed and updated the place of Al Bastakiya on Dubai Creek, and its impact upon the architecture in one of the fastest growing cities in the world. It is now close to 30 years since planning for the preservation and conservation of this important remaining group of windtower houses began, work that was still underway when the first edition was published. Many new domestic and commercial buildings in Dubai and around the Gulf feature the Bastaki style, some successfully, others less so, while its urban scale and form very much influenced some of the detailed planning within Dubai’s Expo 2020. This all needed to be captured and reflected in this new edition, if it was going to be relevant to a new generation of readers and students.

A big difference that can be immediately seen in this edition, is its new format and design. Peter as an architect was very concerned about design and layout from the outset, but it proved a pleasure working with Medina, who were very sensitive to both authors’ comments and worries. The result is a more compact book, much easier to carry around and use as a reference than the original folio edition. The new design is crisp, clear and easy to navigate. We are delighted.

Sustainability is a buzzword right now, and one of the new messages in the latest book. What are you hoping readers will take from this?

Sustainability needs to be much, much more than a buzzword. A great deal has changed in the last fifteen years. There is now far greater global recognition of the effects of climate change and the urgency of tackling their impact on both peoples, the built and natural environments. The Gulf area is particularly vulnerable. This is being recognised, perhaps making it a good testing ground for innovation.

Before the advent of electricity and air conditioning, windtowers offered an entirely passive means of keeping comfortably cool during the hottest summer afternoons. And as the book shows, they worked! Yet of course they had significant drawbacks. They could be very dirty during sandstorms, let in water when it occasionally rained, and could not be effective 24 hours of the day – rather working in conjunction with up-and-downstairs migration, and sleeping on the roof exposed to the night sky. But in the light of our current climate crisis, there has become an increasing awareness that, today, there are important lessons to be learnt from windtowers with their potential for passive cooling, particularly in combination with heat exchangers.

Our original chapter has therefore been substantially extended to consider such research and examples of passive cooling methods being applied to contemporary buildings in the UAE, not least at Masdar in Abu Dhabi, and in Australia. It is a subject that still requires much more research and application – so we ae hopeful our book will encourage that.

How exactly did you come together to research and write Windtower in the first place?

We both knew Dubai before we met. Anne had lived there with her young family from late 1968 until the end of 1971. She had just achieved a PhD in Geography but this counted for nothing – she was simply Umm Ali (in Arabic ‘the mother of Ali’, her eldest son)! She joined the Dubai Women’s Society where she made good friends with local ladies many of whom lived in the Bastakiya quarter nearby. Three summers in Dubai made her sensitive to any air movement which might alleviate the sticky heat – to the change of wind direction at noon and to the cooling effect of the airflow down the windtowers of friends’ houses in the afternoon. In her last year she made preliminary measurements of the effectiveness of a few of these but with the rudimentary equipment available to her was only able to generate hypotheses.

We met in 1973 when Anne was at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and Peter was completing his full-time architectural studies at the Bartlett School, both part of London University. One of Peter’s tutors asked her from her experience to review his final diploma project, a low-cost desert housing scheme near Dubai. Anne was very, but usefully, critical, and out of it developed a long friendship, and an introduction for Peter to undertake his important architectural survey of the since demolished Bukhash windtower house in 1974. This we published together as a monograph, A Windtower House in Dubai, with AARP – Art and Archaeological Research Papers, sponsored by John R Harris Architects with whom Peter was then working, together with a feature for Sherban Cantacuzino, then Editor of the Architectural Review. Together, these formed the beginning of this book.

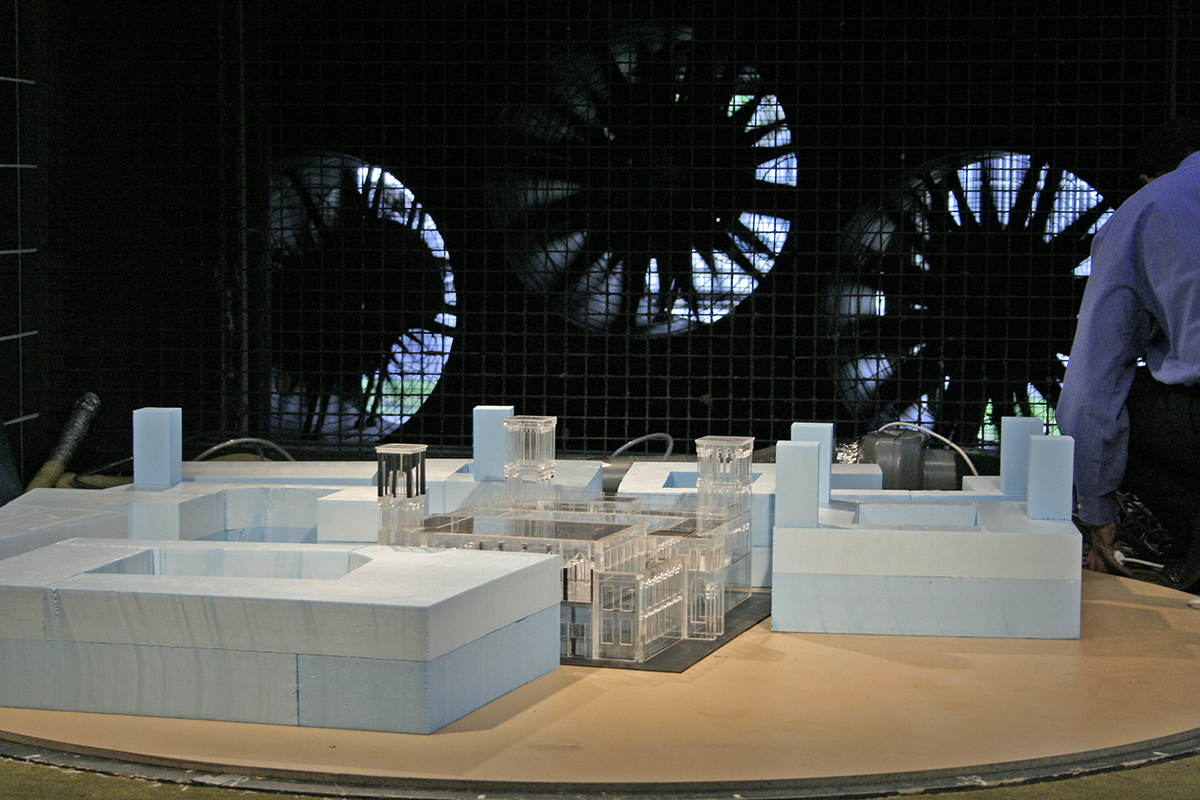

In 1976 Peter left London, and his work in Dubai, to explore working in a less oil wealth privileged environment, and joined Montgomerie Oldfield Kirby Architects (MOK) in Lusaka, Zambia. He only planned to stay two years, but Ron Kirby, a very perceptive and skilled architect, proved inspirational and Peter stayed with him more than four years, before then establishing their own practice in 1980 with another partner in MOK, in a newly independent Zimbabwe. It was only with the beginnings of economic collapse in 2002, that he would close the office, and return with his wife to the UAE. Within a month he was able to meet the Head of the Historic Buildings Section in Dubai Municipality, architect Rashad Bukhash, who introduced himself to Peter as the boy who had held the end of his tape, when they measured his father’s house in 1974.

This serendipitous coincidence lifted Peter’s spirits, from his depression at having had to close his own business and leave what he had expected would remain a permanent home in Harare. He emailed Anne that very same evening, and arranged to visit her in the New Forest in the summer. In long discussion, walking along the beautiful Beaulieu River, we knew we had to expand our original researches and write this book. It just had to be.

How did you undertake your research?

Based on Anne’s extensive academic experience as well as time spent with the Bastakiya community, particularly with women and their children, we began interviews with those she knew, as well as contacts, friends and relatives of Rashad Bukhash. We were particularly anxious to record the memories of the older generation, those people who had lived in the houses, how they had used them and how householders had overseen their construction or alteration. Our interviews were recorded with notes, and often led to other introductions and further interviews. Our original 1974 monograph had focused on just one house, that of Sherif Mohammed Bukhash that, sadly, would be demolished in 1985. We were anxious to compare this with a number of surviving houses, to see whether the architecture and history Peter had recorded was unique to that house, or reflected a general pattern across a broader sample.

While she visited Dubai for this research, Anne was sometimes assisted by Peter’s late-wife Jutta, or sometimes Peter was invited to join a ladies’ majlis as an honorary female for an afternoon. One of the reviews of the first edition remarked that it was rather rare for such a study to include women’s perspectives. Peter continued the interviews between Anne’s visits as work commitments permitted, with male members of the families. We made many friends during this time, which was very special for us as we developed the trust of individuals and the community generally.

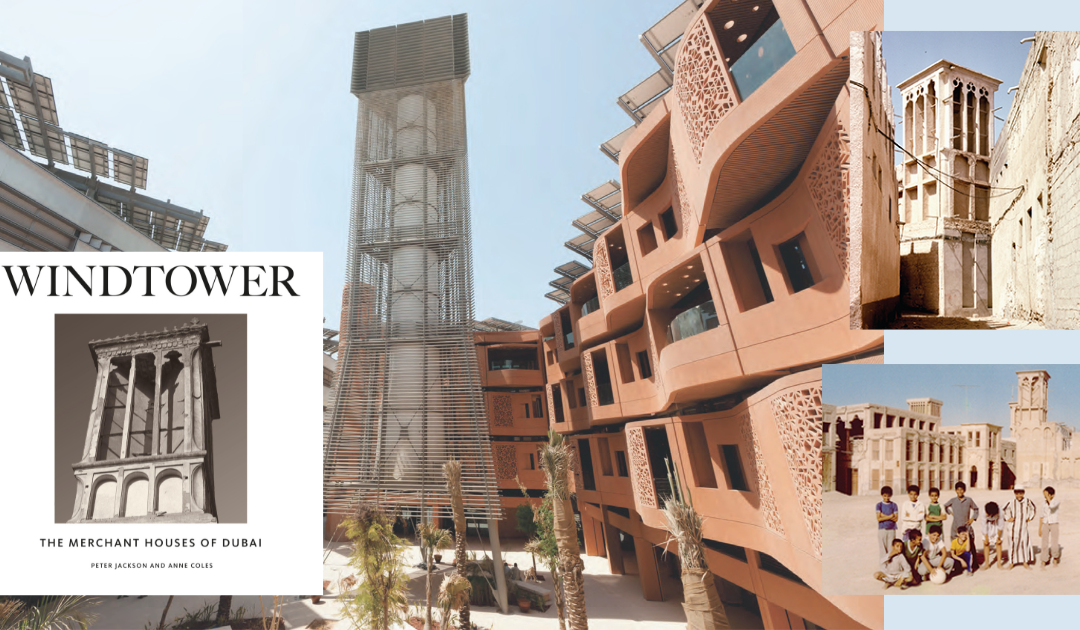

By great fortune Peter was introduced to an Australian scientist, Ian Jones of Vipac Engineers, who were testing designs for the glazing of the world’s tallest building, the Burj Khalifa. Ian became an enthusiastic member of our team, equally fascinated by our subject. He took data from three different wind towers through a full year, taking regular temperature readings, then referring these back to their laboratory in Port Melbourne. There, the data was integrated into wind tunnel testing of a transparent scale model of the Bukhash house. In Sydney, computational models were developed, then finally in Vipac Singapore, resultant comfort levels were assessed. This was truly original and, as far as we are aware, unique research.

Peter was then privileged to make a weekend trip to Bastak, the small town in Iran, from where the community had originated at the beginning of the 20th century. It was a profound experience, travelling with Dr. Eesa Bastaki, and staying in the majlis of his relatives, eating the same food as we were describing in the book, and being hosted in the same way that families hosted guests in the Bastakiya long before there were any hotels in Dubai. All in all, it took us four years to compile all our material and for the book to be designed and edited when it was first published in London by Stacey International.

For this edition with Medina, we were at the beginning of lockdown. It was therefore impossible to carry out any face to face interviews. Initially we were introduced to the new families through the medium of Zoom, but with the advantage that Anne could participate remotely, and we could record the sessions. We repeated the same discipline of checking and cross-checking, with email as our primary method of communication. But it worked, although sometimes slowly. We received great support from the founding members of Al Bastakiya Cultural Centre throughout this process, who really were the drivers for this new edition, not least Rashad, Dr Eesa, and Farid Mohammed al Bastaki who were determined to make it happen in time for the 50th Anniversary of the UAE.

What will you both be focusing on next?

We are very much looking forward to an autumn launch for the Arabic edition by Medina. It is something that we have long wanted to happen. The translation has been undertaken and overseen by the recently established Al Bastakiya Cultural Centre, so you can see that our 48 year-old project is now very much being driven from within the local community, which considers Windtower to be an important contribution to its social record and cultural history.

Thinking of the future: Windtower is a traditional architectural feature, its value specific to certain environmental and climatic regions, but its principles have a usefulness and applicability in other situations. It is an example of how architects, looking ahead, may find other features in traditional homes that are worth exploring and adapting as greater emphasis is placed on sustainability. Ironically, architects already have a renewed interest in air movement for a quite different reason, the use of ventilation in buildings as a means of reducing COVID-19 and similar infections – a quality first emphasized by Florence Nightingale!